Following prolonged political and civil upheaval, the Hanoverian period was a relatively stable time in Britain, characterised by the longevity of its six monarchs who ruled from 1714 through to 1901. However, the founding of a new European ruling dynasty in Britain was not without its problems.

On 20 October 1714, with political unease at a high, an altogether more subdued coronation than usual took place at Westminster Abbey to crown the new king, George I. Just two months before, Queen Anne passed away and left the country without a direct heir, as her closest blood relative was passed over due to the Act of Settlement of 1701. Designed to guarantee Protestant succession to the throne, the act meant that the Catholic James Stuart, son of the overthrown James II, could not become king. Many expected Sophia, Electress of Hanover (the daughter of Elizabeth Stuart), to succeed Queen Anne. Unfortunately, she died two months before Queen Anne, therefore her eldest son George, ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg, inherited the throne instead. In a matter of months, Britain found itself with a Hanoverian king who could barely speak English.

In some ways, it was not entirely George I’s fault that he was so unfamiliar with Britain. In terms of blood relationship, George was not near to the British throne, but by virtue of the Act of Settlement, he was second in line. However, Queen Anne had refused him and his mother permission to visit, as this reminded her of her mortality. Regardless, German-born George I was deemed entirely too foreign by the public, whilst Jacobites believed the Crown belonged to the Stuart bloodline. In the early years of George’s reign, James III, known as the Old Pretender, and his Jacobite supporters plotted and failed to depose the king.

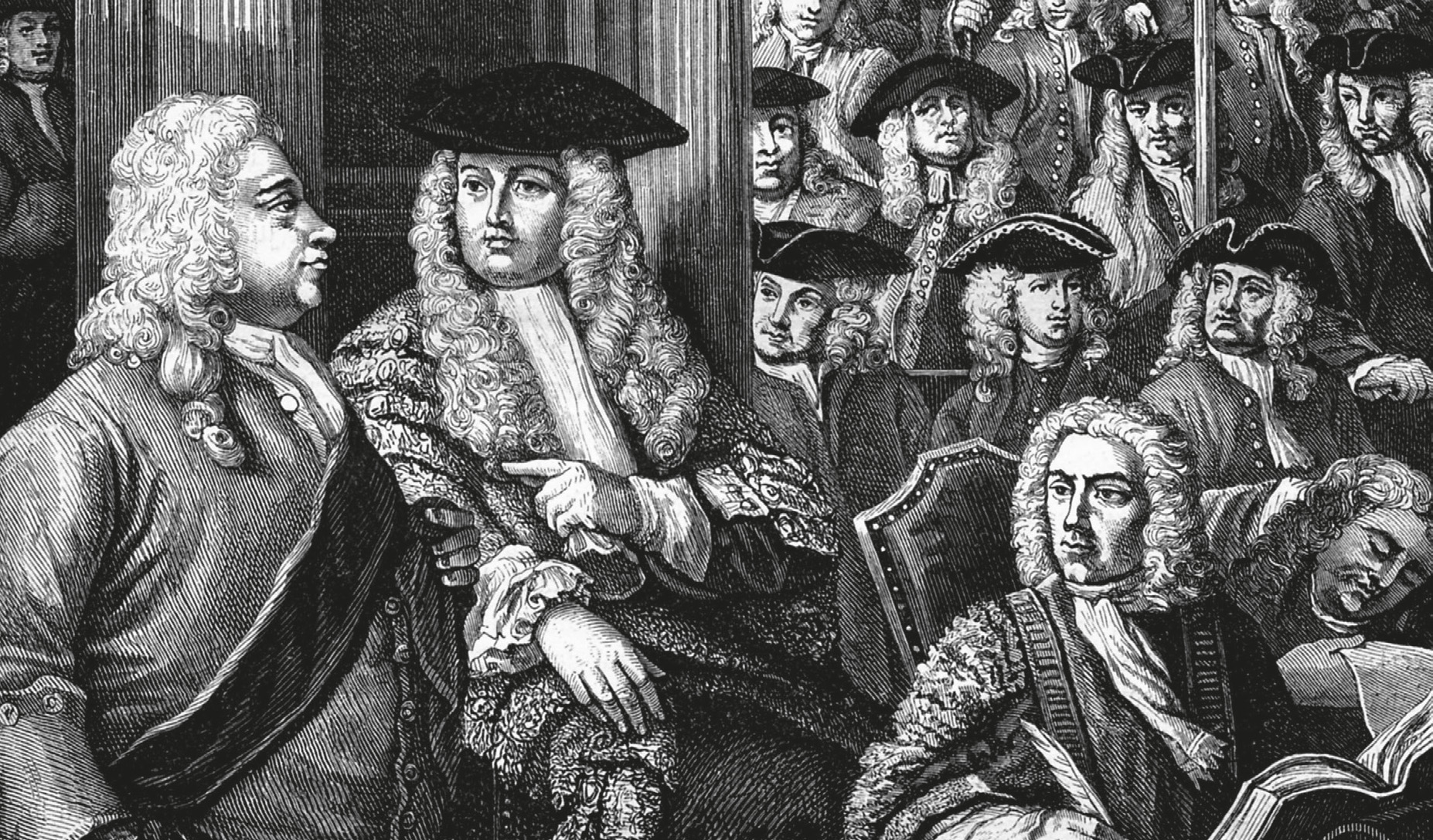

Although the British public never truly warmed to George I, his reign settled and a more modern system of cabinet government slowly replaced traditional royal power. Notably, Britain’s first ‘Prime’ Minister, Robert Walpole, rose to power after successfully helping navigate several ill-advised economic schemes such as the South Sea Bubble, the first stock market crash, which implicated cabinet ministers and the king.

For nearly the whole of George I’s reign, Sir Isaac Newton was Master of The Royal Mint. Known as a ‘great mind’ with a passion for maintaining and improving The Royal Mint’s reputation for integrity and accuracy, his stature as a scientist raised the mint’s profile.

In 1717, because of a significant report by Newton, the value of the guinea at last became fixed at the figure of 21 shillings, following years of fluctuation. A year later, the quarter-guinea (a new gold coin) was issued as an attempt to relieve the worsening shortage in the circulation of silver coins. The new coin bore John Croker’s portrait of George I on its obverse, whilst the reverse was decorated with a cruciform arrangement of the Royal Arms device. Set at a value of five shillings and three pence, it was intended to be a convenient denomination and substitute for the five-shilling silver crown. In reality, the public rejected the coin, not least because of its small size but because the coin’s awkward value created embarrassing situations for mental arithmetic. In the end, only a comparatively small number of pieces were struck.

At this time, people could bring gold and silver bullion to The Royal Mint for coining. These coins could occasionally feature special provenance marks that indicated the source of the bullion from which they were made, so when the infamous South Sea Company deposited some silver bullion, the resulting coins of 1723 included the letters ‘SSC’ on the reverse.

During George I’s reign, the minting of copper farthings and halfpennies resumed following several years of scrutiny surrounding the purity of copper coins. Copper coins were made using rolled copper strips, which were cut into blanks before striking. Struck in high relief, the new issues produced attractive coins but also caused production problems such as weak striking. Made on small diameter thick flans or discs, the very first issues are now well known as ‘dump’ issues, before a thinner, larger diameter was used from 1719.

With a faithfully rendered original coinage portrait of George I appearing on the reverse of the third coin in the collection, The British Monarchs Collection provides an innovative and new way to get closer to early Georgian numismatic history. Discover how we remade history through insights from Laura Clancy, a member of our Product Design team.

British Monarchs

Be Inspired

BRITISH MONARCHS – GEORGE I BEHIND THE DESIGN

Find out more